Workers typically earn more when they live closer to where the jobs are. But years of soaring property prices in cities like Sydney have put housing near city centres and employment areas out of reach for many low- and moderate-income households. According to research firm CoreLogic, many of Sydney’s inner-city areas had a house-price-to-income ratio higher than 10 as of June 2018, compared to the city’s overall ratio of 9.1.

Now research shows that a $7.3 billion government subsidy to build 125,000 affordable rental homes near Sydney’s job and transport hubs could lift disposable household incomes by a total of almost $18 billion over 40 years. Bringing workers closer to jobs centres and transport hubs would benefit both employees and businesses. For property investors, it could boost the housing market in inner-city areas and neighbourhoods near employment hubs.

Bolstering productivity

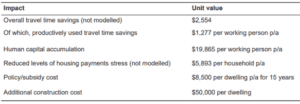

According to a report by the University of New South Wales (UNSW) City Futures Research Centre, building affordable housing closer to jobs would cut travel times and costs to households. Travel time savings could amount to $2.26 billion in today’s dollars over 40 years and help boost labour supply.

The study’s findings suggest that for any given skill, age or gender group, wages are higher for people who live closer to jobs. For example, unqualified workers living close to their workplace earn $11,793 more a year on average, or $56,000 over their lifetime, than those who travel long distances to work. Employees with higher degrees make an extra $41,170 a year, or $425,000 over their lifetime.

Figure 1: Effects of providing better housing outcomes to workers in Sydney

“If we ensure that these individuals had access to affordable housing and had some government grant to bring down the costs of the housing [$8,500 a year over 10 years], then they would be able to save on travel-to-work times, and an average $2,500 per person per year,” says UNSW Visiting Professor Duncan Maclennan, who led the research.

While spending on housing is generally viewed as a social rather than an economic function of governments, the study shows that investing in affordable housing has a strong impact on productivity and economic growth.

“There is a productivity link. Housing policy is not just about redistribution, it’s about growth and productivity too,” says Maclennan.

Addressing the affordability problem

Maclennan calls on governments across Australia to address the housing affordability problem, which he says has disadvantaged younger people disproportionately.

Housing policies typically aim to cap rent at no more than 30% of household income, but the study reveals that low- to middle-income renters in Sydney pay an average of $6,000 a year more than that.

“That’s a huge proportion of their disposable income,” says Maclennan. “It determines not only the savings of younger households, it determines when they become homeowners. It determines how they will accumulate assets throughout their lifetime.”

Treating housing like transport

Maclennan also urges governments to consider housing as economic infrastructure – and treat it just as they would transport investment. He says the productivity gains from building affordable housing suggest that they can have as much economic impact as other infrastructure investments including transport.

City Futures Research Centre Director Bill Randolph believes the research gives momentum to the debate about the economic value of investing in social and affordable housing.

“It also fundamentally shifts the focus to the role of government investment in housing as a key component of economic growth in our cities.”