Australia has one the world’s highest levels of household debt, and research shows that adults who have fallen behind on repayments are cutting back on expenses such as food and utilities. But how pervasive is the impact of debt on spending, and how does it affect the broader economy? Are only financially constrained households making cutbacks?

Economists at the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) recently found that households pare back their spending when their mortgage debt rises – a phenomenon called the ‘debt overhang effect’. The study shows that this effect has spread across households with owner‑occupier mortgage debt – and is not solely driven by households that are financially strained or need precautionary savings. This demonstrates the extent of mortgage debt’s impact and how it could adversely affect businesses relying on consumer spending.

Explains weak spending

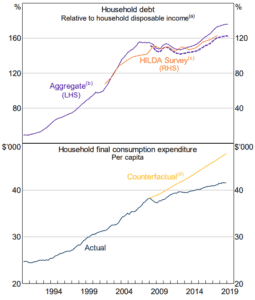

According to the RBA economists, a 10% increase in debt leads households to reduce consumption by 0.3%. Their findings suggest that the rise in aggregate owner-occupier mortgage debt since the global financial crisis has weighed on total spending across the economy.

This can be seen in the numbers today. Australian household consumption has remained weak since the financial crisis, and the RBA has revised down its economic growth forecast for 2019–20 from 2.75% to 2.5% – in part due to uncertainty around household spending.

“We estimate that annual aggregate consumption growth would have been around 0.2 to 0.4 percentage points higher had mortgage debt remained at its 2006 level,” said Fiona Price, Benjamin Beckers and Gianni La Cava, authors of the RBA study.

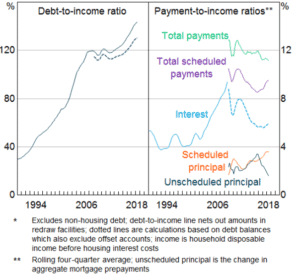

Australia’s total household debt has steadily risen relative to income over the past three decades, driven mainly by mortgages. The ratio rose from around 70% in the early 1990s to 190% in 2018.

Figure 1: Australian household debt and consumption

Figure 2: Debt-to-income ratio for household mortgages*

Spending cuts even as assets rise

Notably, the RBA researchers found that households trim spending even when their gross asset values grow by the same amount as their debt. “In other words, a deepening of household balance sheets is associated with less household spending, even if it is not associated with rising net indebtedness,” said the researchers. “This directly violates conventional consumption theories such as the permanent income hypothesis, which assumes that the composition of household balance sheets does not affect consumption.”

Economic policymakers have generally not expressed alarm over the impact of elevated levels of household debt on the economy.

The RBA, for example, has acknowledged that highly indebted households pose a key risk to financial stability. But it expected these households to potentially cut spending when macro-economic conditions decline – not during favourable or ‘normal’ times. The study’s findings might change this view.

In good times and bad

Not surprisingly, the study found that household spending is more sensitive to debt during adverse economic conditions and housing price shocks. But remarkably, households scrimp even when the economy is doing well. “We find evidence that indebted households reduce their spending by more than other households during adverse macro-economic shocks, such as the global financial crisis, but the negative effect of debt is also pervasive at other times,” said the researchers. This finding might call into question the effectiveness of the Coalition Government’s $158 billion tax cuts package in stimulating the economy. The Government expects more than 10 million individuals to benefit from the package, mainly through refunds starting with this year’s tax returns. But will they spend their windfall or simply use it to cut their debt?