Tightening credit supply has been largely blamed for the slowdown in Australia’s housing market. Adding fuel to this sentiment last year was the banking royal commission. Economists frequently warned about how banks’ tougher lending requirements in response to the inquiry could push house prices further down.

But according to Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Governor Philip Lowe, the slump in house prices has more to do with housing supply and demand. This suggests that growth in house prices would likely stabilise if supply could flexibly adjust to changes in demand.

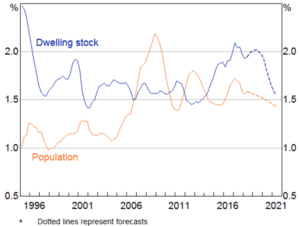

Speaking at The Australian Financial Review Business Summit, Lowe said the correction in prices largely originated in the inability of housing supply to meet demand as population growth surged. Australia’s population grew markedly in the mid-2000s, but it took nearly 10 years for the rate of home building to catch up with demand.

“It took time to plan, to obtain council approvals, to arrange finance and to build the new homes. Not surprisingly, housing prices went up,” said Lowe.

As the number of houses has increased at the fastest rate in more than two decades, prices have moderated. The housing construction market boomed in 2016–17 when about 234,000 new homes were started, according to home building peak body Master Builders Australia.

Figure 1: Growth in population and housing stock

(year-ended)

Data from property consultant CoreLogic shows that national house prices fell by an average of 0.6% in March 2019, which was slightly less than the 0.7% drop in February. Home prices were down 6.9% a year earlier.

Decline in foreign demand also a factor

Lowe said that the dynamics between population and housing supply are most apparent in Western Australia and New South Wales (NSW). In NSW, for example, the recent rate of home building has been the highest in decades. And as population growth has moderated, home values have sunk.

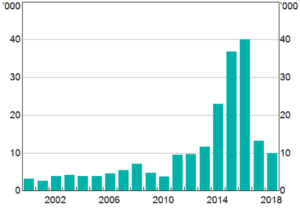

Decline in foreign investor demand has also affected prices, according to Lowe. As Figure 2 shows, foreign buying activity peaked in 2016. Residential real estate approvals from the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) – which foreign investors need to secure before they can buy property in Australia – dropped to 10,036 in 2017–18 from 13,198 previously.

Figure 2: Number of FIRB residential real estate approvals

(financial year)

Foreign demand for housing, particularly from mainland Chinese buyers, nosedived in 2017 following a spate of government-led restrictions on foreign investors. These include less favourable tax treatment, additional or higher stamp duty, and a cap on new development sales. China’s restrictions on the outflow of capital have also affected demand from mainland Chinese investors.

An issue of reduced demand

On the issue of credit supply and its role in the housing slump, Lowe acknowledged that lending standards have tightened in recent years. He said that on average, the maximum amount loaned to new borrowers has dropped by about 20% since 2015.

“This reflects a combination of factors, including more accurate reporting of expenses, larger discounts applied to certain types of income and more comprehensive reporting of other liabilities.”

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority has introduced stricter lending policies in recent years, including stringent mortgage serviceability requirements. This has made bank housing loans out of reach for many potential borrowers.

According to Lowe, lenders became more risk-averse last year – at the height of the banking royal commission – amid concerns about the consequences of failing to meet their responsible lending obligations.

Lowe pointed to evidence that the tightening credit supply has contributed to the slowdown in credit growth. “The main story, though, is one of reduced demand for credit, rather than reduced supply.”