Is Australia’s population growth increasing commute times in our major cities? Is traffic congestion spiralling out of control? Not really, according to a recent study by public policy research centre the Grattan Institute. The study found that the impact of population growth on commute distances and times has been “remarkably benign”, contrary to popular claims.

Australia’s population debate has often revolved around how population growth – mainly driven by overseas migration – has increased commute times and driven people out of city centres. For example, the Chair of Transport Management at the University of Sydney, Stephen Greaves has recently warned that Sydney is nearing a tipping point where its residents would abandon public transport and use cars as the city struggles to deal with its soaring population.

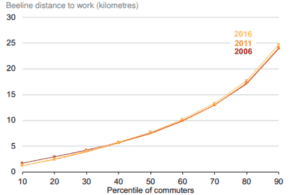

But Marion Terrill and Hugh Batrouney, authors of the Grattan Institute report Remarkably adaptive: Australian cities in a time of growth, say the average commute distances and times in Australia’s major cities have barely increased over the five years to 2016. This is despite the strong growth in the populations of Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, the Gold Coast, the Sunshine Coast, Canberra and Darwin.

Figure 1: Change in commute distance to work in Sydney

Figure 2: Annual change in commute distance relative to population growth, 2011–2016

Commute times have also not changed significantly from 2004 to 2016, but they have slightly increased for longer commutes, according to the authors. In Sydney, for example, a trip that took 60 minutes in 2004 increased to more than 70 minutes in 2016. The commute times are particularly long for workers in Sydney’s central business districts (CBDs), according to a recent study by Deloitte. Their average commute time is 63 minutes – almost 70% longer than the city-wide average.

Spread of jobs a factor

Terrill and Batrouney partly attribute the benign impact of population growth on commuting distances and times to the spread of jobs within major cities. They believe the notion that jobs are concentrated in CBDs and some suburban employment centres is a misconception.

In reality, fewer than two in 10 people work in CBDs, while three in 10 work in suburbs, according to the authors. Parramatta, for example, has only 2.3% of the jobs in Sydney despite being considered the capital city’s second CBD.

“In Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth, three quarters of jobs are dispersed all over the city, in shops, offices, schools, clinics, and construction sites,” say Terrill and Batrouney.

People adapt

Despite their research finding that commutes are not getting worse, the authors acknowledge that the level of congestion in Australia’s largest cities poses problems.

“Trains, buses and trams can be overcrowded, and commuting times can be unreliable,” they say.

However, Terrill and Batrouney argue that the situation is not spiralling out of control and migration has not driven these cities to a standstill.

“People adapt: some change job or worksite, and working from home is on the rise. Some people move house, or even leave the city,” the authors say. “Other people simply accept a longer commute – at least for a time – particularly if they earn a high income.”

At the same time, Terrill and Batrouney call on governments to help people better adapt to congestion problems. They recommend phasing out stamp duty and removing barriers to people and businesses locating where they want to be. In Sydney and Melbourne, they suggest the introduction of congestion charges to discourage drivers who don’t really need to travel at peak hours from using highly congested roads.

“With these changes, the benefits that draw people to live and work close together can outweigh the congestion and crowding that trigger demands to shut new people out,” say Terrill and Batrouney.