Almost a year after the end of the first banking royal commission hearings, the risk to the economy of a credit squeeze looms large.

Economists have warned for months about the risk of banks tightening credit in response to the banking royal commission. They have feared this would worsen softening house prices and trigger consumers to cut back on spending.

Now, after a few years of trying to rein in high-risk lending, financial regulators themselves appear to be concerned about the potential for slowing credit growth to hurt the economy.

The Council of Financial Regulators recently expressed concern about the “overly cautious” approach some banks used in applying lending laws and standards to their approval processes.

“Members agreed on the importance of lenders continuing to supply credit to the economy while they adjust their lending practices, including in response to the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry,” said the council in a quarterly statement in December last year.

The council comprises the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and the Treasury.

Interest-only cap dropped

A clear sign of regulators’ growing concern is APRA’s move to scrap the cap on interest-only residential lending from 1 January 2019. In 2017, APRA introduced a 30% limit on the share of new interest-only home loans to stem soaring property lending.

The decision to drop this cap followed the regulator’s announcement in April 2018 that it would remove the 10% ceiling on investor loan growth.

“APRA’s lending benchmarks on investor and interest-only lending were always intended to be temporary,” said APRA Chairman Wayne Byres. “Both have now served their purpose of moderating higher-risk lending and supporting a gradual strengthening of lending standards across the industry over a number of years.”

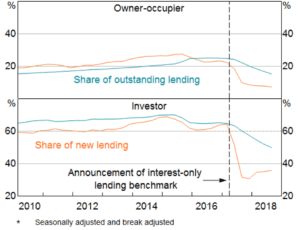

Figure 1: Share of interest-only lending

But as Figure 1 shows, the share of interest-only loans issued to owner-occupiers had been well below 30% before APRA put in place the ceiling. It only declined further after the cap’s introduction.

This suggests the removal of the 30% limit is not likely to encourage or increase interest-only lending to owner-occupiers. Banks are expected to continue to focus on owner-occupiers who are looking for principal and interest loans.

Fallout from inquiry

What seems to be the bigger driver of slowing credit growth now is pressure from the banking royal commission.

The inquiry has raised doubts about banks’ efforts to look into the living expenses of potential borrowers when assessing their serviceability. This has prompted many lenders to toughen their serviceability requirements and slowed home financing.

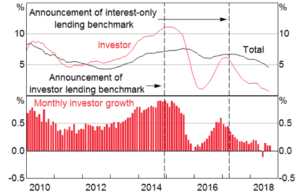

Housing credit growth has moderated since mid-2017. Lending to housing investors, for example, is hardly growing. The RBA estimates that the share of investor housing loans has decreased by 5 percentage points to around 33%.

Figure 2: Investor housing credit growth

(Six-month-ended annualised)

Regulators are now reminding banks about the need to ensure that credit remains available. Federal Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has said that too much risk aversion among banks could impede household spending and investment.

“To avoid these risks, the banks need to balance their responsible lending obligations with the need to keep credit flowing, providing much-needed access to finance for families and businesses,” said Frydenberg in an interview with The Australian Financial Review. “This goes right to the heart of the critical role banks play in the economy.”

Will banks heed regulators’ calls to keep lending? That remains to be seen.