The number of Australians behind in their mortgage repayments is higher than it has been since the fallout from the global financial crisis. This could have implications for banks, especially because it coincides with the ongoing decline in national housing prices. Falling property values could expose banks to losses on home loans.

The share of bank mortgages in arrears is now around the 2010 level of 1%, according to the Reserve Bank’s head of financial stability Jonathan Kearns. This is well below the 2% figure of the early 1990s recession but indicates weak economic conditions, said Kearns at a recent property summit.

Australian banks’ outstanding loans as a percentage of all domestic loans

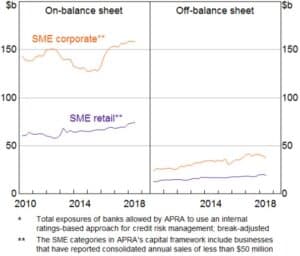

Rising arrears also represent an increased risk to the financial system, given the high value of housing loans in banks’ books.

As Kearns pointed out, mortgages account for about 40% of Australian bank assets. And within property lending, banks’ greatest exposure is to housing loans.

Data from the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) shows that housing loans from authorised deposit-taking institutions totalled $1.65 trillion in 2018, up by nearly 5% on the previous year.

The average balance of an Australian mortgage also continues to increase – from $266,500 in 2017 to $275,500 in 2018, according to APRA. The Reserve Bank’s figure is even higher: $300,000.

Such high levels of debt can make households and the financial system vulnerable if economic conditions greatly decline.

Economic factors and lending standards

Kearns attributes rising arrears to sluggish income growth, falling home prices and increased unemployment in some places.

“Weak conditions in housing markets make it hard for borrowers to get out of arrears by selling their property,” he said.

But economic factors are not solely responsible for the upswing in arrears. Lending standards also contribute, according to Kearns.

Previously, loose loan origination standards allowed borrowers to get larger and higher-risk mortgages, such as those on interest-only terms. This let borrowers who were likely to struggle to repay their loans get a mortgage, contributing to higher rates of arrears, said Kearns.

Now that regulators have bolstered lending requirements, the stronger standards are influencing the rate of arrears, albeit temporarily.

For example, in 2017 APRA introduced a 30% limit on the share of new interest-only home loans. Although it has since scrapped this cap, banks continue to charge higher interest rates on interest-only mortgages. They also assess borrowers more rigorously. This has led interest-only lending to hit a record low of 15% in its share of total lending over the March 2019 quarter, down from its peak of 45% in mid-2015.

“As a result, some borrowers who may have anticipated being able to roll over an interest-only period are finding they cannot,” said Kearns. “Some are then facing temporary difficulty servicing the higher principal and interest payments at the end of the interest-only period.”

A continuing trend

Investment manager PIMCO estimates that monthly repayments for a typical owner-occupier switching from interest-only to principal-and-interest payments will rise by more than 20%. It expects this to push up arrears as the five-year payment window for many existing interest-only borrowers ends in 2019 and 2020.

Over the three years from 2018, around $120 billion in interest-only mortgages is scheduled to switch to principal loans annually, according to the Reserve Bank.

This massive volume is not unprecedented, said the bank. “What is different now, however, is that lending standards were tightened further in recent years.”

Expiry of interest-only period for outstanding securitised interest-only mortgages

(as of December 2017)

With lending standards robust, Kearns doesn’t expect the rising arrears to reach levels that pose a risk to the financial system – as long as overall unemployment remains low.

However, he expects the influence of some of the drivers behind the arrears trend to remain in the near future. “And so, the arrears rate could continue to edge higher for a bit longer.”